The Chicano Artwork Motion represents a kaleidoscopic convergence of aesthetics and politics. When examined at a distance, it may be misunderstood as a singular, cohesive motion with a clearly outlined starting and finish. Any effort to encapsulate the Chicano Artwork Motion, nevertheless, should insist on recognizing the multiplicity and simultaneity of creative visions that got here out of it, in addition to a porousness that facilitated solidarity with artists and teams past the Mexican American neighborhood. This overview focuses totally on artistic manufacturing through the mid-Nineteen Sixties and ’70s as a solution to parallel the actions of el Movimiento, also called the Chicano Civil Rights Motion. (All through this text, “Chicano” is used when referring to paintings created through the historic period of el Movimiento so as to sign the exclusion that ladies and LGBT+ artists skilled, whereas “Chicana/o/x” signifies reference to a recent context.)

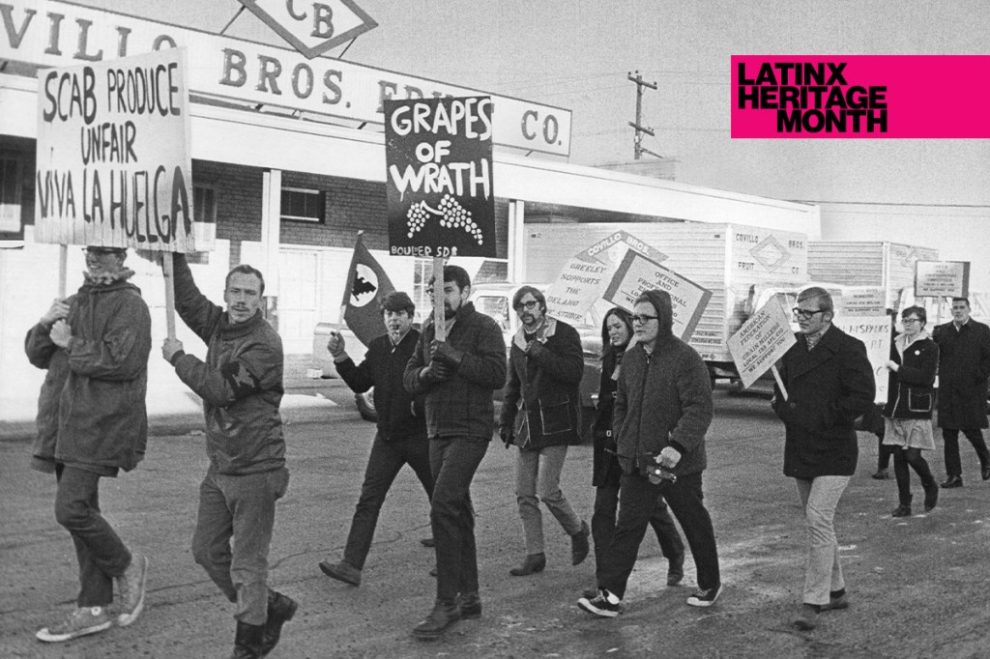

Farmworkers’ strikes that Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta led in 1965 earlier than the formation of the United Farm Employees (UFW) served as a major catalyst for the constructing of a Chicano motion and accompanying types of creative manufacturing. Different struggles inside Mexican American communities continued to form the course of el Movimiento, together with the 1968 scholar walkouts in East Los Angeles and Chicago in response to discriminatory academic circumstances, protests in opposition to the Vietnam Battle led by the Nationwide Chicano Moratorium in 1970, and struggles to revive land rights for Hispano New Mexicans led by Reies Lopez Tijerina. In 1969 the Chicano Youth Liberation Convention, organized by Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales, convened scholar activists from all through america in Denver, solidifying a cohesive sense of Chicano identification, and galvanizing college students nationwide to advocate for themselves via large-scale demonstrations.

Los Angeles Instances journalist Rubén Salazar notably outlined a Chicano as a “Mexican-American with a non-Anglo picture of himself.” The adoption of the time period Chicano as an alternative choice to Mexican American responded to expectations of cultural assimilation with a defiant reclaiming of a time period that originated within the early twentieth century as an insult. Rising together with el Movimientoduring the Nineteen Sixties, self-determination and cultural reclamation underscored the creation of political works all through the Chicano Artwork Motion. Though Mexican American artists have been lively in america previous to el Movimiento, this curiosity in cultural reclamation, the assertion of a politicized identification, and a departure from Eurocentric aesthetic beliefs distinguished this era of Chicano artists from their predecessors.

UFW cofounder Dolores Huerta speaks throughout a rally in California, ca. 1975.

Picture Cathy Murphy/Getty Photographs

Picture Manufacturing as Name to Motion

The UFW acted as an early catalyst for Chicano artwork manufacturing as a instrument for motion constructing. In 1965 Luis Valdez based El Teatro Campesino in California’s Central Valley, and produced brief performances for farm staff laboring within the fields. El Teatro Campesino served as an extension of the UFW’s organizing efforts, hiring visible artists like Carlos Almaraz to color backgrounds and units. The UFW additionally revealed Chicano graphics, establishing Taller de Gráfica Widespread to place out prints, calendars, and different materials that includes UFW imagery. Chicano artists similar to Xavier Viramontes and Carlos Cortez produced prints and posters amplifying requires UFW boycotts each independently and in collaboration with the UFW.

Quite a few Chicano artists, together with Rupert Garcia and Malaquias Montoya, started producing work together with el Movimiento that addressed urgent points, similar to labor struggles, police brutality, state violence, the Vietnam Battle, and deportations. Printmaking and picture manufacturing have been important duties for making certain that data might be shared shortly, successfully, and broadly. Publications similar to El Malcriado, La Raza, and El Grito del Norte drew on the affect of the Nineteen Sixties counterculture underground press and the Black Panther Occasion’s official newspaper. A cohort of graphic designers, illustrators, artists, and photographers produced photos for these publications that made tangible Chicanos’ lived realities and struggles for justice. The satirical cartoons that Andrew Zermeño created for El Malcriado, which ran between 1964 and 1976, confirmed the travails of Don Sotaco, a Mexican American farmworker, who was exploited by his boss, Patroncito, and El Coyote, the labor contractor, as a solution to convey consciousness to the labor circumstances farmworkers skilled.

UFW cofounder Cesar Chavez throughout a rally at Albert Park in San Rafael, California, in 1970.

Bettmann Archive

Maria Varela, a volunteer photographer for La Raza, lived within the Midwest and was recruited by the Pupil Nonviolent Coordinating Committee to file civil rights efforts within the South. All through the ’60s, she traveled extensively with the group, documenting marches and police brutality in opposition to protesters. In 1968 she joined Reies Lopez Tijerina’s group, Alianza Federal de Mercedes, and started documenting vital occasions in el Movimiento, such because the 1969 Chicano Youth Liberation Convention in Denver, in addition to scenes of Hispano communities in New Mexico.

Documentary and avenue images served as a counterpart to Chicano photojournalism, and artists similar to Oscar Castillo, George Rodriguez, and Luis C. Garza moved between these genres. (La Raza’s archives of some 25,000 photos, created through the paper’s run between 1967 and 1977, are actually housed on the Chicano Research Analysis Middle at UCLA; they have been the topic of a significant exhibition, cocurated by Garza, on the Autry Museum of the American West in 2017.) Chicano photographers served as chroniclers of not solely vital occasions, however of the cadences of up to date life: Louis Carlos Bernal’s pictures of communities in Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and California hunt down poignant moments in on a regular basis life that categorical a way of intimacy along with his topics.

Luis C. Garza, Pupil and barrio youth lead protest march, La Marcha por La Justicia, Belvedere Park. January 31, 1971, 1971.

©LUIS C. GARZA/COURTESY THE PHOTOGRAPHER AND THE UCLA CHICANO STUDIES RESEARCH CENTER

Shared Struggles, Distinct Expressions

Very similar to el Movimiento, Chicano artists have been lively throughout a broad geographic vary. Though many artists labored all through the Southwest in Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas, vital Chicano cultural manufacturing additionally happened in Michigan, Chicago, and Seattle. Quite a few works and political actions advocated for cross-ethnic, racial, and transnational solidarity, and Chicano organizers typically collaborated with Black activists, together with the Black Panther Occasion, which served as a reference for the institution of the Brown Berets. Teams in Los Angeles, Chicago, Seattle, and Austin participated in walkouts and marches, advocated for extra equitable public training, and opened well being clinics that served Mexican American communities. Moreover, regardless of the time period “Chicano” referring to Mexican American identification, a number of notable figures throughout the historical past of Chicano artwork, similar to Mario Torero, Herbert Sigüenza, and Sister Karen Boccalero, usually are not Mexican American, suggesting that identification with “Chicano” shouldn’t be certain strictly by ethnicity however by a dedication to the societal points that el Movimiento sought to treatment.

Regardless of Chicano artwork’s identification with a broader motion, the artwork itself is heterogeneous, typically particular to the assorted locales the place a given cohort of artists was primarily based. Inside California alone, the Chicano Artwork Motion has different and distinctive aesthetics within the state’s main cities: San Diego, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Sacramento, Fresno, and Bakersfield. And out of doors California, the artwork scenes within the Southwest, Texas, and Chicago have been equally different. Though recurring motifs and iconography hyperlink distant websites, quite a few artists similar to Chicago-born muralist Ray Patlán met and collaborated with contemporaries exterior their respective geographic areas, leading to a dense nonlinear net of resonance and affect. (The landmark 1990 exhibition “Chicano Artwork: Resistance and Affirmation, 1965-1985,” referred to as “CARA” for brief, historicized 20 years of Chicano artistic manufacturing and featured works by 180 artists, with an emphasis on el Movimiento’s geographic range.)

The revolutionary rhetoric of el Movimiento spurred the formation of quite a few Chicano artwork collectives, similar to East LA’s Los 4 and ASCO, Chicago-based Movimiento Artístico Chicano (MARCH), Movimiento Artístico del Rio Salado (MARS) in Phoenix, and the Texas-based teams Con Safo and Los Quemados. Collectives similar to these pushed in opposition to the mythology of the solitary artist and infrequently produced work in a variety of media and, in some instances, included writers and artwork historians. In Sacramento, the Royal Chicano Air Power supported a broad vary of community-based cultural actions, spanning music, poetry, visible arts manufacturing, and a gallery and bookstore, along with launching a free breakfast program for youngsters. Mujeres Artistas del Suroeste, based by Santa Barraza, supplied a community that created alternatives for Chicanas in Texas to supply and exhibit their paintings.

Many Chicana/o artists have been additionally engaged in constructing constructions to help their work in response to a scarcity of institutional help, assuming the roles of not simply artists, however critics, artwork historians, curators, and humanities directors. All through america, the formation of Chicano artwork collectives coincided with the creation of Chicano cultural organizations that have been steadily based and led by artists, similar to Mechicano Artwork Middle and Self Assist Graphics & Artwork in Los Angeles, Galería de la Raza in San Francisco, and Centro Cultural Aztlan in San Antonio, amongst others, providing devoted area for the creation and exhibition of Chicano artwork at a time when mainstream establishments excluded this work.

David Botello’s 1974 mural Dream of Flight on the Estrada Courts Housing Tasks, forward of its rededication in 1997.

Rick Meyer/Los Angeles Instances through Getty Photographs

Chicanismo and Imagined Mythologies

El Movimiento cohered across the institution of a shared nationalistic identification rooted in Mesoamerican tradition referred to as “Chicanismo,” which provided an alternative choice to Chicanos’ expertise of current between Mexican and American cultures, however by no means feeling a full sense of belonging in both. Via engagement with this previous, Chicano artists situated themselves inside an expansive historical past that preceded colonialism, recommended ties to indigeneity, and provided a deep properly of iconography for adaptation inside a recent context. The reclaiming of the Southwestern US as Aztlán, the mythic homeland of the Aztecs, inverted Chicanos’ and Mexican People’ relationship to the US-Mexico border. For instance, widespread misconceptions that every one Mexican People and Chicanos had just lately migrated to america missed the impression of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo’s designating greater than 50 p.c of Mexican territory as a part of the US, together with what later grew to become the states of California, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and a part of Wyoming. Because of this, this invocation of Aztlán asserted not solely that Chicanos have all the time been current on the land now referred to as the US, however that the border itself had crossed them, and never the inverse.

The UFW emblem provides an early reference to Mesoamerican tradition in Chicano artwork. Developed in 1962 by Cesar and Richard Chavez, the emblem encompasses a semiabstract black eagle that references the parable of an eagle holding a serpent touchdown on a nopal (prickly pear) that led to the institution of Tenochtitlán because the capital of the Aztec empire. Moreover, the eagle’s geometric type recollects the structure of a stepped pyramid. This reclaiming of a Mesoamerican previous drew upon the Mexican authorities’s embrace of mexicanidad in state-sponsored cultural productions through the Mexican Revolution, which embraced mestizaje, or ethnic and cultural mixing of Spanish, Indigenous, and African peoples, as a part of the creation of a brand new nationwide identification. Inside each mexicanidad and Chicanismo, Mesoamerican tradition served as a malleable touchstone to anchor identification, somewhat than present a set historic reference level.

Chicano Park in San Diego.

Training Photographs/Residents of the Planet/Common Photographs Group through Getty Photographs

Inventing a New Iconography

Along with claiming the Mesoamerican previous, Chicano artists regarded to historic figures and cultural manufacturing of the Mexican Revolution, embracing figures similar to Emiliano Zapata, and girls troopers referred to as adelitas, and finding out the works of Mexican artists similar to Los Tres Grandes (David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco), Frida Kahlo, and the printmaker Jose Guadalupe Posada. Chicano artists additionally critically reexamined stereotyped figures, such because the pachuco and pachuca, and retold present and historic occasions via artworks that questioned hegemonic narratives. Many early Chicano artworks featured imagery of Mexican revolutionaries and Aztec warriors and deities, similar to Quetzalcoatl, and references to up to date struggles in depictions of the UFW flag or farmworkers.

Ester Hernandez, La Virgen de Guadalupe Defendiendo los Derechos de los Xicanos, 1975.

©1975 Ester Hernández/Smithsonian American Artwork Museum

Although machismo prevailed in Chicano artwork circles, Chicana artists produced work that mirrored the complexity of their very own expertise, reimagined cultural representations of femininity, and recovered historic figures similar to Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz and La Malinche. Notably, Yolanda López, Ester Hernández, and Patssi Valdez reclaimed imagery of the Virgin of Guadalupe, displaying the sacred icon as an embodied determine who can run, follow karate, and seem as strange girls. Queer artists similar to Mundo Meza, Teddy Sandoval, Joey Terrill, and Robert “Cyclona” Legorreta witnessed the Homosexual Liberation Motion and produced experimental and different iconographies that positioned them as each Chicano and queer whereas interrogating the exclusion of each identities, as seen in Terrill’s “Clones” sequence and Sandoval’s sequence of portraits that reclaimed the homophobic slur “maricón” by picturing his topics sporting T-shirts, made by Terrill, with the time period printed throughout the chest.

An aesthetic method distinctive to Chicano artwork is the strategic utilization of supplies and imagery drawn from the experiences of working-class Mexican People. In 1989, Tomás Ybarra-Frausto theorized this method in his essay, “Rasquachismo: A Chicano Sensibility,” which reframes rasquache, a classist time period, as a web site of empowerment and inventiveness. Most importantly, Ybarra-Frausto argues that rasquachismo can’t be lowered to a set of stylistic qualities, however that it’s emblematic of a selected angle and style. In 1992, Amalia Mesa-Bains wrote “Domesticana: the sensibility of Chicana rasquache,” which articulated the importance of aesthetic practices by Chicanas that have interaction the area of the house as a important response to not solely dominant tradition, however gendered expectations inside Mexican American communities as properly. Within the many years following their publication, rasquachismo and domesticana stay generative frameworks that artists, students, and curators proceed to elaborate on and interact.

Rupert García, Frida Kahlo (September), from Galería de la Raza 1975 Calendario.

©1975 Rupert García/Smithsonian American Artwork Museum

One other enduring expression of Chicano artists’ engagement with the previous is the commentary of Día de los Muertos (Day of the Useless). Starting within the Seventies at Self Assist Graphics & Artwork in East Los Angeles and Galería de la Raza in San Francisco, artists started to analysis traditions associated to Día de los Muertos and adapt them to a recent context, creating ofrendas (choices) and papel picado (minimize paper) decorations, and organizing processions. In San Francisco, trainer and activist Yolanda Garfias Woo taught kids and most of the people about Día de los Muertos traditions beginning within the late Nineteen Sixties. Garfias Woo labored with artists at Galería de la Raza to start out an annual Día de los Muertos celebration; the one in 1978 was notably devoted to Frida Kahlo, and featured an ofrenda that was a collaboration between René Yañez, Carmen Lomas Garza, Amalia Mesa-Bains, and different artists. This piece departed from the ornate type that may sometimes be created for the event, and extra carefully resembled an intimate sacred area throughout the residence, concurrently chatting with the growth and adaptation of a conventional type and recovering a major cultural touchstone. Custom and reinvention typically melded within the processions organized by Self Assist Graphics within the ’70s, during which contributors dressed as calacas (skeletons) marched alongside adorned lowriders.

The affect of Mexican artwork on Chicano muralists is seen in such motifs as portraits of great figures, political allegory, and references spanning historic eras. Chicano artists Judith F. Baca and Emanuel Martinez traveled to Mexico to review with Taller Siqueiros. After Martinez returned to Colorado, he painted his first mural, La Alma/The Soul (1978), close to the housing tasks within the La Alma Lincoln Park neighborhood in Denver. In 1974 Baca started work on The Nice Wall of Los Angeles, a monumental mural depicting a multi-perspectival historical past of California painted on the concrete sides of the Tujunga Wash phase of the Los Angeles River. The half-mile-long Nice Wall, which originated as a mission to beautify the positioning, notably engaged a variety of collaborators, together with youths, different artists, and an array of consultants on California historical past. (The Nice Wall is at the moment present process an growth to convey its imagery as much as the current, with a $5 million grant from the Mellon Basis; an exhibition on the Los Angeles County Museum of Artwork that ended this previous July featured Baca and her staff portray a number of of those new panels on-site.)

Oscar “Eagle” passes by a number of the murals he helped arrange in 1973 that adorn the houses in Estrada Courts in Boyle Heights in 2013.

Al Seib/Los Angeles Instances through Getty Photographs

Very similar to The Nice Wall, many early Chicano murals have been painted in an effort to create vibrance in missed environments, together with residential contexts, similar to Estrada Courts in Boyle Heights, in East Los Angeles, and Balmy Alley within the Mission District of San Francisco. In different websites, similar to Chicano Park in San Diego and Lincoln Park in El Paso, Texas, artists painted murals on constructions supporting the freeways so as to reclaim area for the communities residing there. The Mujeres Muralistas, a gaggle of Chicana and Latina painters lively in San Francisco, contradicted assertions that ladies couldn’t deal with the bodily calls for of mural portray and expanded the visible lexicon of images depicted in murals with scenes of girls, meals, and households. Moreover, ASCO, a collective that disidentified with elements of the Chicano artwork motion, adopted a satirical method that embraced political motion via avant-garde efficiency, dressing as murals that had turn into bored and walked away from a wall, in Strolling Mural (1972), and protesting the exclusion of Chicano artwork at LACMA with Spray Paint LACMA (1972).

For Chicano artists, this rediscovery, reclamation, and reinvention of the previous provided a corrective to the historical past (and artwork historical past) they discovered in academic settings, which privileged a Eurocentric viewpoint and rigidly noticed a corresponding aesthetic hierarchy during which portray and sculpture have been valued above all else. Though Chicano artists drew upon a variety of formal and stylistic languages all through their work, amongst them abstraction, Conceptualism, Minimalism, Pop artwork, psychedelia, and punk (amongst others), the motion not solely referred to as for the creation of recent imagery and iconography, however invited a reconsideration of which aesthetic varieties have been related and worthwhile. Within the many years following el Movimiento, the ideological commitments and political identification that animated the early years of the Chicano Artwork Motion have repeatedly developed, with veterano and rising artists alike extra just lately figuring out as Chicano/a/x. In doing so, they proceed to develop and redefine the contours of Chicanx artwork. This ongoing work of reimagining runs concurrently with scholarly efforts to comb via tangled historic threads, and in doing so, get better unseen archives, narratives, and dimensions of Chicanx artwork historical past.

Add Comment